Child Development: Insights from a Mother, Buddhism, and Psychology

Mothers Teach Us the Initial Connection to Life

Mothers are our first teachers about the fundamental connection to life, an irreplaceable method…

Fascinating Story about Mothers from Nobel Prize-winning Author Toni Morrison

My fascinating story about mothers comes from Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison and her novel “”The Bluest Eye.”” It narrates the life of a young girl, Claudia, growing up in Ohio in the same town as Toni Morrison.

Claudia’s mother is strict and often scolds her. One day, when Claudia falls ill with a cold and cough, her mother scolds her harshly before tucking her into bed. Later, she applies Vicks to Claudia’s chest, wraps her neck, and covers her with blankets. However, Claudia throws off the blankets, and her mother, in anger, scolds her again. Claudia, crying and feeling guilty for being sick, eventually falls asleep. That night, as she coughs, she feels her mother’s hand on her forehead, adjusting her covers. In these moments, Claudia senses her mother’s concern. Later, Claudia associates these memories with a person who didn’t want her to die.

The signal that someone cares for us and doesn’t want us to die is a powerful one, often expressed by mothers in various ways. Claudia’s sense of love from her mother wasn’t through words, but through her mother’s hands. Many of us can relate to this. For me, it’s the same. The love I felt from my mother wasn’t much in her words, but in her actions. When I recall warm times with my mother, I think of the things she did, not what she said.

Like Claudia, my mother would scold me too. Once, I came home with a bleeding hand from playing at a construction site. My mother scolded me, which felt unfair at the moment – I was hurt and bleeding, yet I got scolded. But what mattered was her bandaging my wound, and now I understand that her anger, like Claudia’s mother’s, stemmed from concern, worry that I had been in danger and that it might happen again if she didn’t intervene.

But these aren’t my only memories of my mother. I remember her sewing clothes for me. Standing beside her sewing machine, watching her work skillfully, I felt proud and fortunate to have a caring mother. I also remember her cooking, especially making banana cakes in the kitchen. I loved those cakes and always felt like she made them just for me.

I’ve observed similar expressions of love in action with my wife, Yoshiko, and our children. She’s a good cook but never baked until our children grew a bit. Her first attempt at baking was disastrous. The cakes, placed too close together on a tray, merged into one big lump during baking. They were hard, dry, and not sweet enough. But the kids loved them, probably because they were made by their mother’s hands. Within a year, Yoshiko’s baking skills improved significantly. But the important thing about her cakes wasn’t their taste; it was that she made them for our children, not for me or herself.

Psychology of Child Development in Western Culture

The psychological connection between mother and child reflects many aspects of Buddhism. Western child development psychology tells us that initially, there is no distinction between mother and child. As the child develops in the womb, the mother and child are one. There is no separation; both are connected.

Therefore, when a newborn enters the world, it doesn’t sense any separation from the mother or the surrounding world. Everything remains connected. The awareness of individuality and self-identification doesn’t come naturally at birth. These are developed over time through a process psychologists call separation and individuation. Margaret Mahler refers to this process as “”the psychological birth of the child.””

First comes the physical birth, where physical separation from the mother occurs dramatically and noticeably. Then follows the psychological birth, a subtler and slower process. Here, we develop a sense of individuality separate from the mother and the world, forming a personal identity. Western psychology stops there, but Buddhism asks us to go further.

As children, we need to build a sense of self. It’s how we learn to function in the world. But as adults, we must go beyond individuality and see the interconnectedness with the world. We need to reconnect. Dogen Zenji, the founder of the Soto Zen sect in Japan, reminds us that to study Buddhism is to study the self, and to study the self is to forget the self in merging with something greater.

To develop correctly as a Buddhist, we must experience ourselves as something more than just our individual selves or egos. We need to reconnect with something greater. Perhaps we start by rediscovering the connection within our family, particularly the special bond between mother and child. Then, we extend this connection and interdependence to our community and eventually to the entire world. We do this harmoniously, creating harmony within the family and then with the world.

It’s intriguing to note that the psychological distance between mother and child differs across cultures. In Japanese culture, this distance is lesser than in Western traditions. I first noticed this when I visited Japan years ago. Dining with my wife’s relatives, we naturally discussed the similarities and differences between the U.S. and Japan. As I was introduced as a student of child development, a Japanese dinner companion, seemingly puzzled, asked me, “”Is it true that in the U.S., parents are tough on their children?”” I must admit, I was surprised by the question.

I had always assumed that Japanese parents were stricter. Didn’t they require their children to study rigorously and attend school even after regular hours? Feeling something unusual, I asked for clarification. He responded, “”Can you confirm this, but I heard that in the U.S., parents put their children in separate rooms and let them sleep alone?”” This question opened my eyes to a new perspective. Indeed, I had never thought about it, but I had to acknowledge it as true.

I realized that the Western approach to child-rearing, promoting early separation between mother and child, reflects a value system that emphasizes individualism and independence. Westerners tend to focus on the distinctiveness and independence of children. In contrast, other cultural groups, like Japan, value connection and interdependence, thus maintaining less physical distance between mother and child.

Traditionally, Japanese mothers sleep with their children and carry them around in a sling for a longer period than some Westerners might find usual. This difference became apparent when an elderly neighbor kindly expressed concern that our second son, Noah, wouldn’t learn to walk because Yoshiko carried him all the time. This seemed unnatural to him. Research also indicates that Japanese mothers tend to discuss relational topics with their children more than European-American mothers, who often address personal issues and individual matters.

These cultural differences in the psychological distance between mother and child, and the differing worldviews they reflect, can make it more challenging for us in the West to understand Buddhism. A colleague teaching religion once told me that Zen Master Kyozan Joshu asked what aspects of the Western worldview make Buddhism hard to grasp for them. The master seemed to ponder the difficulty of teaching monks in both Japan and the U.S., feeling that teaching in the U.S. was much more challenging. Part of the answer to his question may lie in how we care for our children.

The Western style of parenting focuses more on individuality and independence than collective-oriented cultures. As a result, it creates difficulties for us as adults when trying to abandon separateness to become an interconnected part of the vast, formless Dharma. However, from my own experience, I know we can achieve this! We can start to let go of separateness and feel ourselves as a part of the existing Dharma. And to some extent, we might thank our mothers for this initial lesson of connection.

Kurt Kowalski

Translated by Lại Như Bằng.

(Source: Giác Ngộ Newspaper)

Sản phẩm bạn có thể quan tâm

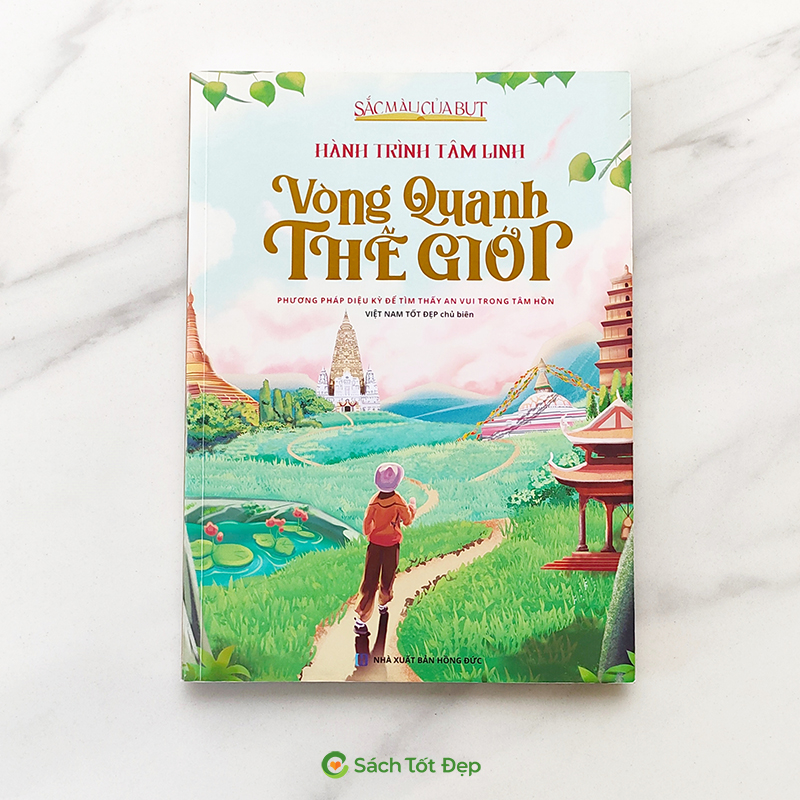

The Colors of Buddha: A Spiritual Journey Around the World

Coloring book

135.000đ

Let’s play with Sen Sun: Mid-Autumn Festival

Coloring book

30.000đ

Wisdom Combo: 5 books + 3 special gifts

Coloring book

280.000đ

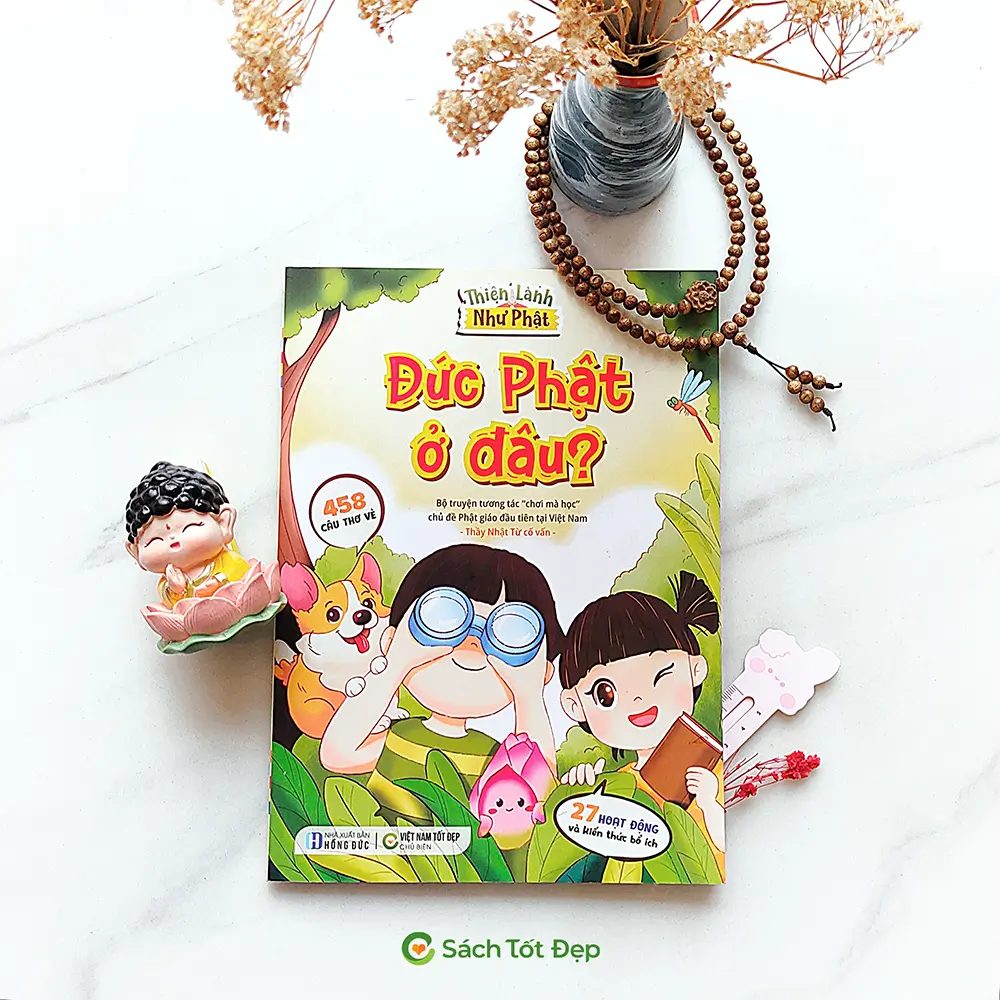

Buddha’s Little Explorers: Where is Buddha?

Interactive book

59.000đ